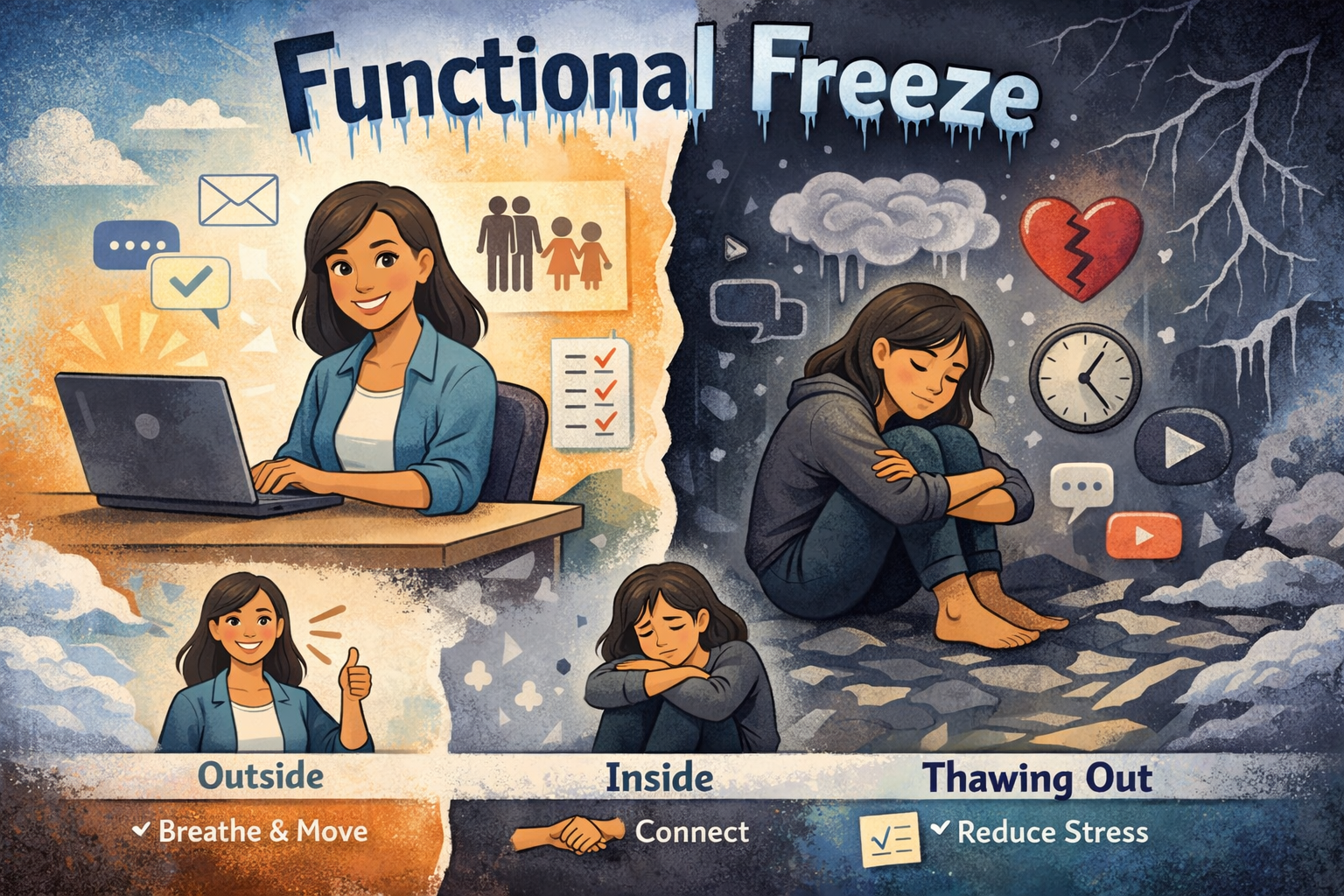

Some days, we seem perfectly okay on the outside. We answer social media posts, reply messages, get our work done, care for our families, and even manage to smile when needed. But inside, it can feel like something is missing. Joy feels distant. Making decisions is hard. We keep going, but still feel stuck.

This feeling is often called functional freeze. As one source puts it: “productivity masks your pain.”

What is a functional freeze?

Functional freeze is not a formal medical diagnosis. It is a descriptive term people use when we are functioning outwardly but feel numb, foggy, disconnected, or on autopilot inside.

A functional freeze can occur when stress lasts too long, when life feels emotionally unsafe, or when our bodies learn that slowing down and just getting by feels safest.

As one psychologist says, “It’s not a moral failure or a character flaw; it’s a nervous system doing its best to cope.”

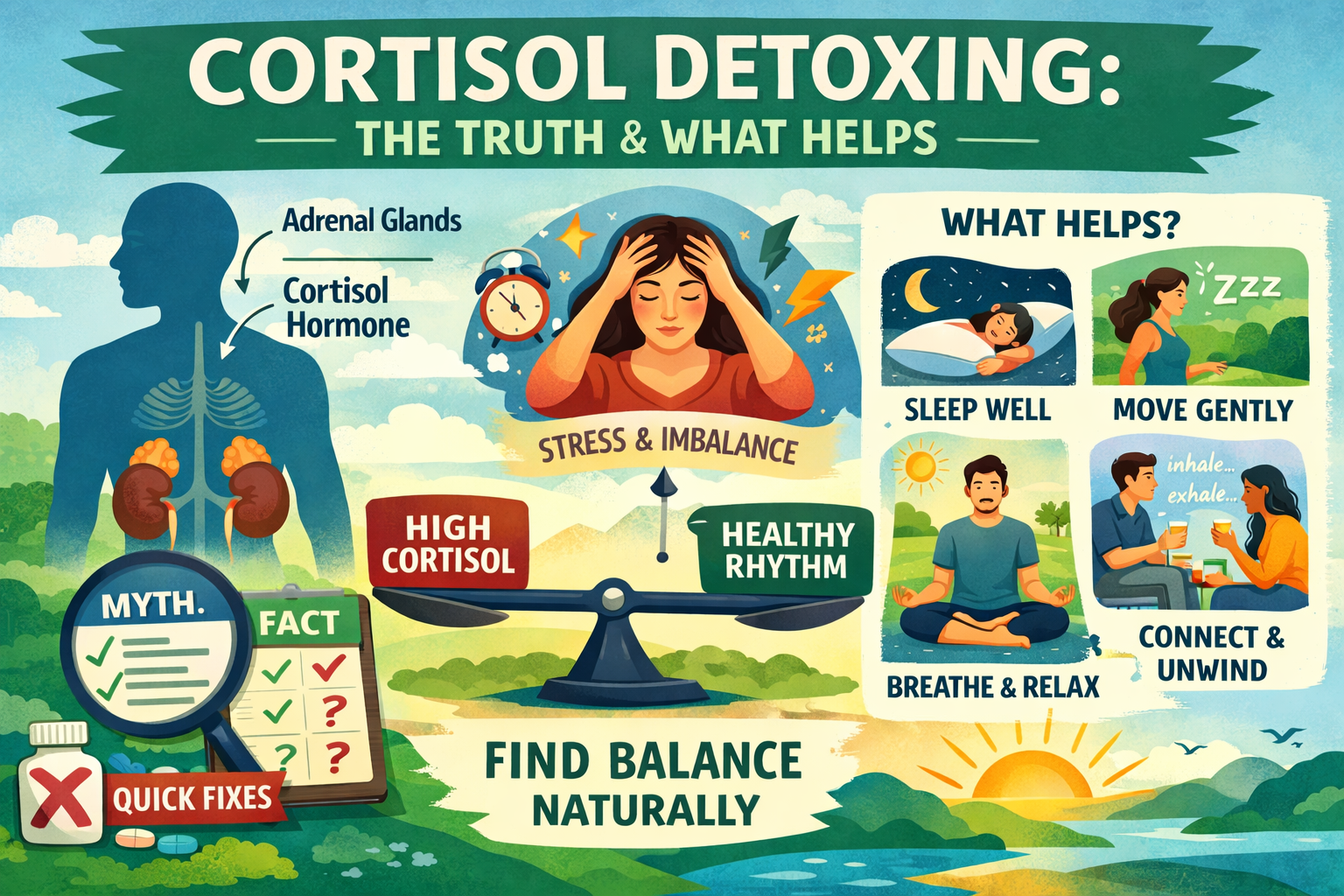

What is happening in our body and brain?

When we sense a threat, our bodies can switch into survival modes like fight, flight, or freeze. Research shows that freezing is not about being lazy or passive. Learn more about the polyvagal theory and freeze response.

“Freezing is not a passive state but rather a parasympathetic brake on the motor system.”

Simply put, our bodies might use a kind of “brake” to keep us from burning out. Some people call this a shutdown feeling. Polyvagal theory describes it as an immobilized state, where the heart rate slows and the body feels flat or frozen.

Functional freeze is like a socially acceptable version of freezing: we keep showing up.

Functional freeze vs. burnout vs. depression

At this point, it is important to be kind to ourselves and seek clarity. Burnout often shows up as exhaustion, cynicism, and feeling less effective.

Depression is a diagnosable condition. It can include deep hopelessness and, for some people, thoughts of suicide. A functional freeze can look like depression, but it is usually seen as a stress response to feeling overwhelmed. One clinical source says that suicidal thoughts are a clearer sign of depression than functional freeze.

These experiences can overlap. If you have felt “frozen” for weeks or months, it is a good idea to talk to a qualified professional.

Signs we might be in functional freeze

Here are some common patterns people notice:

- We handle the basics, but feel “checked out.”

- We experience brain fog, indecision, or decision fatigue.

- We feel emotionally numb, with little joy or motivation.

- We avoid tasks, not because we are busy, but because we feel stuck inside.

- We scroll, binge-watch, or zone out to escape feeling overwhelmed.

- We may look calm, but inside we feel both “wired and tired.”

It helps to remember: “Functional freeze is often missed because people can still function.”

What research tells us about deeper “freeze” states

While “functional freeze” is a newer term, there is a lot of research on freeze states in general. A major review explains that freezing is an organized survival state linked to specific brain and body mechanisms, not a personal weakness.

Trauma research on tonic immobility—a more intense, involuntary freeze response—shows that in a study of 184 people with chronic PTSD, many experienced immobility during trauma and when re-experiencing it. This immobility was linked to more severe PTSD symptoms.

Another study found that tonic immobility was strongly linked to post-assault memory problems, self-blame, anxiety, and depression—sometimes even more than other common trauma markers.

The takeaway is simple: when our system freezes, it can leave a real mark. Instead of feeling ashamed, we can learn to work with it. Do not shame it. We work with it.

How we can “thaw” without forcing ourselves

Our system usually does not respond well to harsh pushing. It responds better to small, safe signals.

1) Start with orientation: Name five safe, neutral things you see. This tells the brain, “Right now is different.”

2) Use micro-movement: Roll shoulders, stretch hands, take a short walk to the window. Tiny movements are often more effective than dramatic changes.

3) Breathe for safety, not performance: Breathe in through the nose, longer exhale through the mouth, and repeat for 1 to 2 minutes. A longer exhale activates the parasympathetic system and often helps the body soften.

4) Add co-regulation: Spend time with a calm person, sit near someone safe, or even listen to a steady voice. Social connection is a powerful nervous system cue.

5) Reduce the load with compassion: The body chooses shutdown for a reason. We can ask: what is one small responsibility we can delay, delegate, or simplify today?

When should we seek extra support?

When functional freeze lasts for weeks, affects sleep, relationships, or work, or if we notice hopelessness or thoughts of self-harm, professional care matters. Consider reaching out to a mental health professional or contacting a crisis helpline if you need immediate support.

A functional freeze is not a weakness; we do not have to carry it alone.